In the final instalment of this series, I want to wrap up our terse discussion of formal languages and their interpretations by stretching out the analogy as much as possible. Perhaps one day, we will have a satisfactory formalisation of praxeology that will render this analogy empty. Until then, we must make do with this.

Edit: here are the links to the first and second parts!

To sparsely summarise what we have laid out so far:

Formal systems are tools that reduce our thinking to machine-verifiable symbol manipulation.

First-order formal languages are constituted by an Alphabet, a Symbol Set, and manipulation rules for constructing and augmenting strings of symbols.

They only derive any meaning from what we imbue them with; more formally, they must be interpreted.

Notions of satisfaction and consequence were also developed, which the reader can look back on to peruse. We can now eat the pudding to see its proof.

Praxeology and Thymology

The ‘proof’, so to speak, of the action ‘axiom’ (that humans act — they employ scarce means to achieve valued ends) is often understood to be via negativa, i.e. by demonstrating that denying it would be self-defeating; the denial of the axiom is itself an action, aimed at some end, and employing some means. Only the radical sceptic does not face direct self-defeat, though it could be considered a mark against a position to have to retreat to radical scepticism to dispute it.

Since transcendental proofs in general do not constitute defeaters for sceptical scenarios, however, it is more fruitful to see the ‘axiom’ as an invitation of sorts to interlocutors to look and see for themselves that the praxeological categories are universal, i.e. constitutive of every possible action.

Every action is indeed aimed at some end using some means. This is a constitutive fact about action. It is not a contradiction to speak of an action aimed at no end in particular, it is simply false. More accurately, it is a category error. It is meaningless to speak of an action that isn’t aimed at any particular end. Actions conform to our categories in the sense that any phenomenon that didn’t would not be an action for us. Such phenomena as involuntary breathing or blinking are not actions but merely behaviours. Thus, the axiom is indeed synthetic a priori.

Much like Kant’s categories of experience, there are also the categories of action; every action is aimed at some end, employing some scarce means (at least the actor’s time and body), and subject to success or failure, with uncertainty. The explication of these categories and the consequences of their particular structure is the task of praxeology. If the categories are the grounds for any possible experience, the praxeological categories are the grounds for any possible action. The relevance of the consequences of such an identification of our experiential synthesis is a pragmatic question; the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

Just like the categories require the schemas to “latch on” to their subject, just like the strings of our group-theoretic language require an interpretation to be semantically sensible, praxeology requires thymology to apply itself to particular actions. The formal conditions of praxeology are the necessary structure of any phenomenon that is to be perceived by us as an action, but in identifying the content, the flesh that is held up by the formal skeleton, we need thymology. Without this content, we are merely left with an empty formalism. Thoughts without content are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind.

Transcendental Deduction and Performative Contradictions

As mentioned above, arguments for the validity of the action axiom are often patterned as “performative contradictions”. The thrust of the argument is that it is contradictory to deny the action axiom or argue against it because denying and/or arguing is itself an action. Thus, in making the argument, the interlocutor demonstrates precisely what they mean to deny - a performative contradiction. Since any attempt to argue for the negation of the action axiom must fail in this manner, the argument goes, one must accept the axiom. The power of Logic compels you.

The inference process, however, if it must command some normative capability, is subject to the same paradox as Carroll’s. The argument via negativa is simply insufficient for the task. A pragmatic appeal to the applicability of the praxeological theorems, and thus to the immanent application of the categories of action to particular actions, is simply unavoidable.

Transcendental arguments, in general, only demonstrate doxastic necessity; in other words, they demonstrate what we must believe to be true as opposed to what is. For pragmatic purposes, however, given that truth-discovery is an activity we engage in, revelation of doxastic necessity is sufficient. To borrow an analogy from Roderick Long, analysing human action without the teleological categories is like playing chess by hitting a ball across a net. That would not be chess. That would not be praxeology. Such proclamations simply do not count (for us) as statements about human actions.

In a broad sense, this is akin to Kant’s primacy of practical reason over pure reason. The argument via negativa is even structured like a transcendental deduction. Thus, the action axiom in praxeology is akin to the synthetic unity of apperception in the Kantian system: the lynchpin of the entire program.

There is not enough space here for a thoroughgoing defence of the discursive formulation of Transcendental Idealism from Stroudian attacks. The implications for Hoppe’s famous “argument from argument” will be the subject of a future post.

The Problem of Irrational Action

One consequence of the formalist paradigm, troubling to some, is that the notion of “rational action” is rendered oxymoronic, and thus that of an “irrational action”, contradictory. This seems to fly in the face of ordinary experience; don’t people act irrationally all the time? The resolution is not particularly satisfactory, but unfortunately, just correct - the term “rational” is being used in a technical sense here, much like the term “rational number”. Even seemingly “irrational” actions are, from the perspective of the praxeologist, either rational or not actions in the first place.

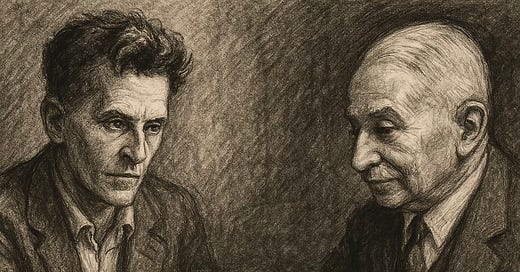

Thought can never be of anything illogical, since, if it were, we should have to think illogically... It used to be said that God could create anything except what would be contrary to the laws of logic. – The truth is that we could not say what an ‘illogical’ world would look like... It is as impossible to represent in language anything that ‘contradicts logic’ as it is in geometry to represent by its coordinates a figure that contradicts the laws of space or to give the coordinates of a point that does not exist.

-Wittgenstein.

“Buy narrow, sell wide”

In this consideration, Roderick Long brings up a Wittgensteinian example of an odd tribe that values wooden blocks not for their volume but rather for their width. Although it may seem idiosyncratic, the example is substantive in characterising, e.g. Dutch book arguments for the “irrationality” of certain beliefs. Let us state it in full and examine it for ourselves.

People pile up logs and sell them, the piles are measured with a ruler, the measurements of length, breadth, and height multiplied together, and what comes out is the number of pence which have to be asked and given. They do not know ‘why’ it happens like this; they simply do it like this: that is how it is done... Very well; but what if they piled the timber in heaps of arbitrary, varying height and then sold it at a price proportionate to the area covered by the piles? And what if they even justified this with the words: “Of course, if you buy more timber, you must pay more”?... How could I shew them that – as I should say – you don’t really buy more wood if you buy a pile covering a bigger area? – I should, for instance, take a pile which was small by their ideas and, by laying the logs around, change it into a ‘big’ one. This might convince them – but perhaps they would say: “Yes, now it’s a lot of wood and costs more” – and that would be the end of the matter. – We should presumably say in this case: they simply do not mean the same by “a lot of wood” and “a little wood” as we do; and they have a quite different system of payment from us.

The alleged irrationality, of course, is in the fact that an Alert Kirznerian Entrepreneur (AKE) could buy up piles of wood, spread them out, and sell them back to make a clean profit. The analogy with “money pump” arguments is perhaps clear now. Superficially, this seems embarrassing for the praxeologist. Must we defend the behaviour of this tribe as being “rational”?

YES.

From a wertfrei standpoint, buying up the wood piles and spreading them out is simply an act of production. The AKE is no more “exploiting” this tribe than his counterpart producing bread from wheat is. In a reductive sense, all production is mere rearrangement. The piled-up wood is simply a higher-order good that is converted to a consumer good (the pile spread out) with an application of human labour and time. The praxeologist qua praxeologist is agnostic to the normativity of consumer preferences, he simply takes them as given in his analysis.

The only sense in which such behaviour could be considered “irrational” would be if the tribe were sleepwalking, in which case we would not consider them to be acting at all. Thus, the “buying” and “selling” of wood piles would no longer be economic activity, since the teleology would be deflated out of the phenomenon. We would put on our psychological hats instead and investigate the cause of their peculiar symptoms, but we would not construe them to be acting.

Rationality is neither a psychological claim about empirical regularity nor a heteronomous commandment imposed from without. It is constitutive of all action insofar as it is action.

Defending Diminishing Marginal Utility

As a final application of our discursive thesis, let us tackle an objection to the Austrian formulation of the law of diminishing marginal utility, which can be found here. Our foil will be David Friedman’s critique.

David Friedman states the succinct case for DMU, quoting Rothbard.

Thus, if no units of a good (whatever the good may be) are available, the first unit will satisfy the most urgent wants that such a good is capable of satisfying. If to this supply of one unit is added a second unit, the latter will fulfill the most urgent wants remaining, but these will be less urgent than the ones the first fulfilled. Therefore, the value of the second unit to the actor will be less than the value of the first unit. Similarly, the value of the third unit of the supply (added to a stock of two units) will be less than the value of the second unit. … Thus, for all human actions, as the quantity of the supply (stock) of a good increases, the utility (value) of each additional unit decreases.

(Rothbard)

His objection to this demonstration takes the form of a counter-example. We will not stress the positive argument, but merely dissolve the counter-example through the discursivity thesis (“Praxeology without thymology is empty, thymology without praxeology is blind”).

This is Rothbard’s proof of the principle of declining marginal utility. To see why it is wrong, consider tires for my car. The marginal utility of the third tire, the benefit of having three tires instead of two, is less, not more, than the marginal utility of the fourth tire. Rothbard’s proof works as long as each unit is used for a different and unrelated purpose, since you rationally choose to achieve the most important purposes first. It breaks down any time having the earlier units makes it possible to use later units in ways they before could not have been used.

(Friedman)

The absence of praxeology here ‘blinds’ Friedman to the theory of marginal utility, so to speak. He conceives of units in terms of physical quantities rather than units of a homogeneous stock as seen by the acting person. This point is brought up in the next quotation from Rothbard in the essay (emphasis added).

It is possible that a man needs four eggs to bake a cake. In that case, the second egg may be used for a less urgent use than the first egg, and the third egg for a less urgent use than the second. However, since the fourth egg allows a cake to be produced that would not otherwise be available, the marginal utility of the fourth egg is greater than that of the third egg.

This argument neglects the fact that a “good” is not the physical material, but any material whatever of which the units will constitute an equally serviceable supply. Since the fourth egg is not equally serviceable and interchangeable with the first egg, the two eggs are not units of the same supply, and therefore the law of marginal utility does not apply to this case at all. To treat eggs in this case as homogeneous units of one good, it would be necessary to consider each set of four eggs as a unit.

(Rothbard)

Friedman summarises:

The fourth egg is not equally serviceable with the first because having the first three eggs increases the options for the fourth — it can be used to make a cake. The second glass of water is not equally serviceable with the first because it is not needed to quench my thirst. The fact that possession of earlier units changes what later units can be used for is what makes marginal utility decline — or, in the case of eggs and tires, increase.

(Friedman)

Physical homogeneity is not the criterion that characterises “units” of a supply of goods. Neither is the criterion of homogeneity purely psychological, however. Properly understood, it is praxeological. Machaj points out that the appropriate conception of homogeneity is rooted in the counterfactual conditions of any given action. Objects are homogeneous insofar as they serve the same end. This conception of homogeneity is rooted in the means-end framework of the acting person. Thus, in the tires/eggs example(s), the unit in question is properly understood as a set of four tires/eggs. The possession of earlier physical units only completes the praxeological unit when the fourth physical unit is added.

To speak of the ‘marginal utility’ of the fourth physical unit is a category error — the notion of marginal utility only properly applies to units of a homogeneous supply of goods in the praxeological sense, not the physical one. To understand what the appropriate ‘unit’ is in any given case, we must use our faculty of understanding, or verstehen. In other words, the praxeological law of diminishing marginal utility is empty without thymological understanding, i.e.

Praxeology without thymology is empty, thymology without praxeology is blind.

Friedman also brings up a secondary counter, however. Rothbard seems to contradict his careful analysis in a later section of the book.

Later in the book, Rothbard writes:

This individual has, of necessity, a diminishing marginal utility of money, so that each additional unit of money acquired ranks lower on his value scale. This is necessarily true.

If I have $999 in my possession, the addition of $1 may allow me to purchase a $1000 widget that I value more than anything else I could purchase with a budget of $999. Once again, however, the appropriate “unit” of money in question would be $1000, not $1. The appropriate application of the praxeological categories allows us to dissolve the apparent tensions in all such examples.

I do take issue, however, with Rothbard’s presentation in one aspect — it is preferable to present the law of diminishing marginal utility if one considers the diminution of supply rather than an increase. This is because the increased supply can allow for an expansion of the possibilities frontier, while a diminution can never do so. Thus, the law of diminishing marginal utility can be more cleanly conceived of as the fact that the end given up when supply is diminished must be the least valued end that can still be satisfied.