Utilitarianism for Animals, Kantianism for Humans

Or, how I learned to stop worrying and love soy

First time here? I'm dabchick—unequal parts economist, philosopher, and mathematician, with an incurable habit of connecting dots and a Quixotic fantasy of being a renaissance man. After years of vanishing into online rabbit holes, I've developed a lust for thought and a preference for first-principles reasoning. Each week, I challenge myself to write, hoping that someone, somewhere, may marginally improve their world model. It may even be me. That’s what the comment section is for!

Sorry, I missed last week’s post — I have no excuse.

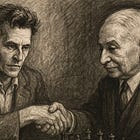

In his magisterial Anarchy, State, and Utopia (ASU), Robert Nozick briefly considers the ethical treatment of animals as a quick aside regarding the nature of rights as side constraints on actions. The notion of side constraints is brought up to contrast against typical utilitarian conceptions of morality as obliging us to maximize “utility” in some sense. He creates a position that he terms ‘Utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for humans’ which he ultimately dismisses, but I believe to be right on the mark regarding how we should think about morality concerning animals, though I would (and will) quibble with the details. Although the section in ASU is quite short in itself, I will quote from it extensively, regardless, to flesh out (no pun intended) my position. The original formulation of U4AK4H is as follows:

(1) maximize the total happiness of all living beings; (2) place stringent side constraints on what one may do to human beings. Human beings may not be used or sacrificed for the benefit of others; animals may be used or sacrificed for the benefit of other people or animals only if those benefits are greater than the loss inflicted.

My quarrel with Nozick’s formulation will also resolve an objection he raises to what is essentially Robin Hanson’s argument against veganism, namely

One ubiquitous argument, not unconnected with side constraints, deserves mention: because people eat animals, they raise more than otherwise would exist without this practice. To exist for a while is better than never to exist at all. So (the argument concludes) the animals are better off because we have the practice of eating them. Though this is not our object, fortunately it turns out that we really, all along, benefit them! (If tastes changed and people no longer found it enjoyable to eat animals, should those concerned with the welfare of animals steel themselves to an unpleasant task and continue eating them?) I trust I shall not be misunderstood as saying that animals are to be given the same moral weight as people if I note that the parallel argument about people would not look very convincing. We can imagine that population problems lead every couple or group to limit their children to some number fixed in advance. A given couple, having reached the number, proposes to have an additional child and dispose of it at the age of three (or twenty-three) by sacrificing it or using it for some gastronomic purpose. In justification, they note that the child will not exist at all if this is not allowed; and surely it is better for it to exist for some number of years. However, once a person exists, not everything compatible with his overall existence being a net plus can be done, even by those who created him. An existing person has claims, even against those whose purpose in creating him was to violate those claims.

Why the ‘specie-ist’ distinction that we intuitively make? I propose that it is due to the uniquely human trait of goal-directed behaviour and the possibility of argumentative communication. Our existence and mutual recognition of each other as rational beings imply side constraints on the actions we may legitimately pursue. That is to say:

We cannot philosophize without being able to speak (and write) and to listen (and read). Indeed, this cannot be denied at pain of contradiction, because the denial itself would have to come in the form of words and sentences.

To quote Nozick again, but this time from an unrelated section — “Individuals have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights).” The justification of the side-constraints thesis will be deferred to a future article, but let us stipulate for now that there are indeed such side-constraints. Thus, we assume K4H and focus on the veracity of U4A in this article.

Why Utilitarianism?

Even if the reader can stomach (no pun intended) the uncontroversial thesis that animals cannot engage in rational, argumentative communication to resolve what may be done with the rivalrous resource that is their respective bodies, there are two opposing objections to the animal utilitarian thesis. One could dispute that animals, too, have rights given their sentience. Of course, such an argument would only apply to animals that are indeed sentient, thus excusing the consumption of jellyfish and bivalves, but the objector could easily grant this caveat.

However, mere sentience is not a sufficient criterion for rights. If we accept the thesis that rights theory delineates a set of side-constraints on actions, i.e. things that one may not permissibly do, regardless of the end they intend to pursue, then they would only have traction for beings that are capable of acting — sentient but non-rational beings, whatever moral consideration they may have, do not have rights.

Another objection to the animal rights thesis is the almost universally accepted notion that “ought implies can”. That is, we do not hold moral agents to ethical standards that would be impossible for them to meet. Consider:

It would be absurd to assign moral blame to gay people for natural disasters.

It would be absurd to say that you were responsible for the death of someone halfway across the world because you did not teleport there to prevent it.

It would be absurd to declare that the housing industry is morally culpable for the deaths of billions of bugs.

The third case is no different than the first two — it is a simple application of the principle that ought implies can. Thus, the case for animal rights is nonsense on stilts.

The other, more radical, objection to U4A denies animals any moral consideration whatsoever. While I have no clever argument to skewer this skeptical position, I hope the reader will be sufficiently aghast at the consequences of such a thesis. It would entail, for instance, that stuffing kittens into a bag and drowning them in a river is not an immoral action.

The argument for veganism in modern society, which we are building up to, only requires you to accept the premise that causing unnecessary and easily avoidable pain and suffering to animals is wrong. Factory farming delenda est.

Here’s a question that shouldn’t be difficult for anyone with a moral compass: should babies be ground to death in blenders? Should they be suffocated in bags? If your answer is no—as no doubt it should be—you should oppose this horrific practice done to billions of baby chicks. Are you really in favor of paying for the blending of babies?

The case for animals as moral patients (as opposed to moral agents) is relatively straightforward, as argued by Tom Regan in ‘The Case for Animal Rights’. Although Regan argues for such welfare or well-being considerations as merely an intermediary step, U4AK4H advocates can get off the train before its final destination. Surely animals feel pain, have desires, and perhaps in some cases even rudimentary thoughts. However, they categorically do not demonstrate linguistic behaviours. The complete inability to engage in such behaviour disqualifies animals from having any sort of “rights” in the sense that humans do.

Name the trait

The famous ‘Name the Trait’ argument is perhaps the one I have thought about the most. Although I have come to accept the moral force of veganism, I don’t think the argument stands. Essentially, it attempts to appeal to marginal cases, or the gradient between humans and non-human animals, to derive a contradiction between an interlocutor’s treatment of humans as opposed to their treatment of animals. The argument is undeniably powerful — one must bite uncomfortable bullets to escape it.

However, the simple response to NT is to name the trait — the ability to engage in rational communication. The a priori of communication, so to speak, is the grounds for human rights and is also a sharp criterion distinguishing man from non-human animals. To sketch K4P roughly, if there is any disagreement regarding the use of any rivalrous resource (in particular human or non-human animal bodies), then rational actors can communicate and potentially arrive at a peaceful resolution of the dispute. Rational beings are ‘ends in themselves’, mostly because it is only of rational beings that we can even stipulate means-ends schemas. Readers interested in this framework may consult my previous essay on the topic here.

Regan draws on a distinction between moral “patients” and “agents” to make his argument for animal rights. To quote Jan Narveson's summary:

A moral agent is, of course, one which acts, and in particular acts (or at least can act) in the light of moral requirements and other moral considerations. A "moral patient," by contrast, is one which we can affect by our actions, for better or worse, but which cannot itself act in response to moral considerations at all. Such, of course, would be animals. And one way of putting the basic question of this controversy is this: What are our duties, if we have any at all, to moral patients? (And, of course, why?)

If animals are non-rights-bearing moral patients to whom one can reasonably assign notions of well-being, pain, and suffering, then the most plausible ethical framework concerning animals seems to be some form of hedonic utilitarianism. ‘Mere’ utilitarianism because they do not have rights, and hedonic as opposed to preference utilitarianism because animals do not have rational preferences in the first place, only inclinations. Your indoor cat may want to run outside, but it is better to disallow it from doing so. Thus hedonic as opposed to preference utilitarianism.

Veganism

One relatively trivial consequence of the U4AK4H thesis (just the U4A part actually) is that one ought to be vegan. If it is wrong to torture animals for minor gustatory pleasures, then of course one cannot support modern factory farming. However, U4A does not necessarily commit one to strict veganism. It is possible, in theory, to obtain eggs and dairy “humanely”, but existing practices do not meet this low bar. Even Robin Hanson’s argument may have some teeth if it weren’t for the dystopian actuality of factory farming. It may in some cases be better for animals reared for meat to live a short life than not exist at all, but the overwhelming majority of farmed animals (yes, including eggs and dairy) live lives of such unimaginable cruelty that it would be better for them to never have existed. Conscientious carnivores do exist, such as Charles Amos:

Many questions remain — if it is possible to live without consuming animals or animal products, why not do so? How much moral culpability do consumers have for unethical production practices, if it is possible (on the U4A thesis) to obtain such products ethically? I am not sure, but it cannot be zero. After all, it is ultimately consumer sovereignty that ordains factors of production along particular lines. The vegan movement is an attempt to steer this force toward lesser cruelty.

In a future article, we will go over objections to veganism, answering them from the perspective of the U4AK4H thesis. In particular, the claim to be defended is that the purported benefits of meat, eggs, and dairy are overstated and trivial compared to the immense pain and suffering that they cause. While K4H prohibits any violent action against vegetarians and omnivores, U4A nonetheless compels me to peacefully convince others to make the switch.

We will also talk about the one exception to my veganism — cats.

For now, it should suffice to watch this video of a vegan DESTROYING Charlie Kirk with FACTS & LOGIC.

I'd say it's our existence and mutual recognition as *irrational* beings that implies side constraints on actions. Animals strike us as non-rational, which is why we think they don't count as much. What binds humans together, and avoids the argument from marginal cases, is that we're systematically irrational.

Of course, everyone is systematically irrational in a slightly different way -- and that's what we call a personality. And it's because we don't see, say, cows as having personalities that we think they're interchangeable and thus not proper subjects for deontological side constraints. But as soon as, say, a dog has a distinctive personality, we're much more inclined to put it under the Kantian umbrella.

Fascinating read and awaiting the next part! While I personally lean towards a reducterian approach primarily motivated by sustainability rather than animals rights, I am strongly reminded of Tobias Leenaert's argument in his book "How to Create a Vegan World". He suggests that the only truly compelling reason to go fully vegan is a commitment to animal rights, since other goals like sustainability, climate change, and health can often be achieved through non-vegan diets.